Catalonia referendum: Does the region want to leave Spain?

ERC VALLS

ERC VALLS

Catalonia's separatist government has staged a referendum on leaving Spain - against the wishes of the national authorities. With a population of 7.5 million, its capital is the proud city of Barcelona.

The Spanish leadership has rejected the vote as illegal and the courts have ordered a halt. Spanish police have arrested senior Catalan officials, seized ballots and raided key regional buildings, as well as polling stations, in an attempt to stop it going ahead.

Catalans have taken to the streets in protest. So what has stirred this hunger for independence - and could it happen?

How did we get here?

Catalonia is one of Spain's wealthiest and most productive regions and has a distinct history dating back almost 1,000 years. Before the Spanish Civil War it enjoyed broad autonomy but that was suppressed under decades of Gen Francisco Franco's dictatorship from 1939-75.

When Franco died, Catalan nationalism was revived and eventually the north-eastern region was granted autonomy again, under the 1978 constitution.

A 2006 statute granted even greater powers, boosting Catalonia's financial clout and describing it as a "nation", but Spain's Constitutional Court reversed much of this in 2010, to the anger of the regional authorities.

Angered by having their autonomy watered down as well as by years of recession and cuts in public spending, Catalans held an unofficial vote on independence in November 2014. More than two million of the region's 5.4 million eligible voters took part and officials declared that 80% had backed secession.

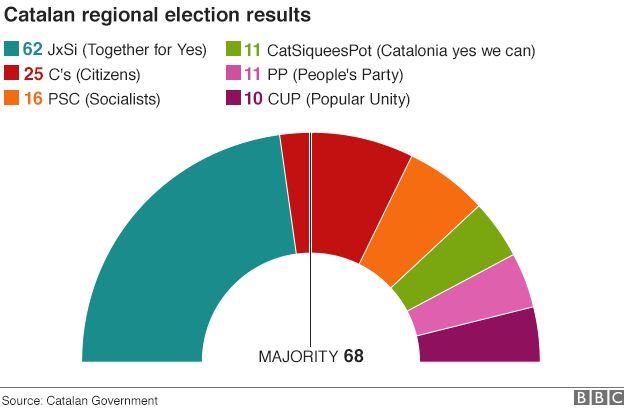

Separatists won Catalonia's election in 2015 and set to work on holding a binding referendum, defying Spain's constitution, which states that Spain is indivisible.

What was the question?

The Catalan parliament enacted its own law in a vote on 6 September. There was just one question on the ballot paper:

"Do you want Catalonia to become an independent state in the form of a republic?"

And there were two boxes: Yes or No.

Under the controversial law, the result is binding and independence must be declared by parliament within two days of the Catalan electoral commission proclaiming the results.

JAUME CLOTET

JAUME CLOTET

Catalan President Carles Puigdemont insisted that "no other court or political body" could suspend his government from power.

How did that go down in Madrid?

Badly. Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy condemned the vote as illegal: "I say this both calmly and firmly: there will be no referendum, it won't happen."

REUTERS

REUTERS

Acting at Mr Rajoy's request, the Constitutional Court suspended the lawpassed by the Catalans. The Spanish government also moved to take control of the region's finances and policing.

Catalan officials involved in organising the vote were arrested, some 10 million ballot papers impounded, and websites informing Catalans about the election were shut down.

Catalonia's own police force, the Mossos d'Esquadra, was ordered to accept the command of Spain's paramilitary Civil Guard to stop the vote taking place.

"Spain has de facto suspended the self-government of Catalonia and has applied a de facto state of emergency," President Carles Puigdemont has complained.

What happened on the day?

Voting did take place in some form in some areas, but more than 400 people were injured when police used force to try to stop the referendum.

The national authorities had brought in 4,000 police from outside Catalonia to help thousands of local Mossos police and national officers to keep security and stop the vote.

Parties loyal to Spain who won about 40% in the 2015 Catalan election boycotted it, so the No vote is likely to be tiny and hugely unrepresentative. And yet, it will be hard for Madrid to deny Catalan secessionists have a case if there is a strong turnout.

Under the Catalan government's referendum law, a declaration of independence has to take place within 48 hours of a Yes vote. That seems a highly unlikely step now, and Carles Puigdemont has said "a unilateral declaration of independence is not on the table".

Do Catalans really want independence?

Pro-independence supporters have certainly produced large-scale demonstrations in favour of secession. A million people turned out in Barcelona for the national day on 11 September.

EPA

EPA

Opinion polls are hard to come by but the clearest indication came in July, when a public survey commissioned by the Catalan government suggested 41% were in favour and 49% were opposed to independence.

We know that 2.2 million voters backed independence in the previous vote in November 2014, and that coalition of separatist parties called Junts pel Si (Together for Yes), with the support of a radical left-wing party, the CUP, won 48% of the vote in 2015 elections.

There was a sense that support for independence may have been ebbing, but the hardline strategy of the Spanish authorities to stop the vote going ahead may equally have re-energised backing for the vote itself to take place.

Does Catalonia have a good claim to nationhood?

It is certainly long-lived. It has its own language, a recorded history of more than 1,000 years as a distinct region, and a population nearly as big as Switzerland's (7.5 million).

It also happens to be a vital part of the Spanish state, locked in since the 15th Century, and - according to supporters of independence - subjected periodically to repressive campaigns to make it "more Spanish".

Catalonia's grievances with Madrid

Barcelona has become one of the EU's best-loved cities, famed for its 1992 Summer Olympics, trade fairs, football and tourism.

But Spain's 2008 economic crisis hit Catalonia hard, leaving it with 19% unemployment (compared with 21% nationally).

It is one of Spain's wealthiest regions, making up 16% of the national population and accounting for almost 19% of Spanish GDP. But there is a widespread feeling that the central government takes much more than it gives back.

Does Madrid really rip the region off?

It does appear to take more than it gives - though the complexity of budget transfers makes it hard to judge exactly how much more Catalans contribute in taxes than they get back from investment in services such as schools and hospitals.

According to 2014 figures, Catalonia paid €9.89bn more into Spain's tax authorities than it received in spending - the equivalent of 5% of its GDP.

Meanwhile, state investment in Catalonia has dropped: the 2015 draft national budget allocated 9.5% to Catalonia - compared with nearly 16% in 2003.

But some argue that is a natural state of affairs in a country with such regional economic disparities.

Is there room for compromise?

Spanish ministers say they are happy for Catalans to celebrate and demonstrate on Sunday and the government in Madrid is opening the door to possible constitutional reforms. They may be ready to offer more money and greater financial autonomy, Spanish Economy Minister Luis de Guindos told the Financial Times.

But that may not be enough for Carles Puigdemont and a Catalan leadership that has spent months preparing a path for independence.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario